Sample Essays

Signs to Good Words

by Tess Jacobson

My mother, father, and brother vanished. What happens now? I lack the words to express my sorrow, my future and…

Mid-sentence, I struggled to convey this agony. My imagination was congested. I tried to force myself into the mind of my protagonist, but couldn’t find the words. So I dropped my pencil and unfinished story. I turned to sign language. If I couldn’t write or speak the suffering, I could sign it and capture the words. With thought as the conductor, my hands obediently brought the scenario to life, forcing me to lace my feet into the shoes of the character and bring his feelings to life in the way I had imagined: authentic, yet silent. “The growing lump of panic in Collin’s throat suddenly choked him before plummeting to the pit of his stomach where it filled him with overwhelming desolation and absorbed all other traces of sentiment.” Sign gave me these words.

American Sign Language started with a casual comment from an eighth grade teacher. Visual learners tend to acquire skills in learning sign language. As a visual learner, I decided to give it a try. The more I engaged in this culture of people who, unlike me, are deaf, I couldn’t let go. So, I searched to find a way to learn this language on my own.

Sign complements another love of mine—writing. I didn’t begin writing because I was a naturally good wordsmith, but because I needed it. My imagination lusts for boundlessness and I credit my seventh grade English teacher for facilitating this discovery. She gave the class a five-minute required daily writing period with one condition: no one but the writer would see his or her scribblings.

At first, I wasn’t exactly producing masterpieces of originality. I scrawled on the pages not knowing what to write or, if I was feeling extra imaginative, I would describe the classroom. However, regardless of the topic, there was something liberating about taking part in an activity without limits or direct instructions to follow. As soon as I discovered my affinity for this independent, unrestricted expression, my imagination was released from its shackles and I produced work that compelled me to break the class rule and show my work to others.

Today I love to write—poems, essays, stories, lab reports, term papers. My fire for this art form is all inclusive. From analyzing Hollywood’s portrayal of America during the Great Depression to describing an original biology experiment on the psychological impact of color and light, I crave opportunities to speak my mind—soundlessly and tangibly. I’m enticed by most anything that makes me a better writer, which is one reason I’m drawn to sign language. Without the two, I would have been limited without ever knowing.

The words to describe the unfathomable emotional situation in my short story seemed unattainable because I had never experienced the circumstances. Sign guided me to go below the exterior of explaining “how sad” something could be and helped me extract the visceral aspect of grief, allowing me to connect with the character, and making him a part of reality—not just an imaginary sketch. Sign forced me to reach the core of what my character could have felt, not just the mere essence, giving the words the aesthetic animation that speech cannot provide. The captivating gestures embedded in sign language are almost as riveting as the feeling that comes with giving vocabulary a physically moving existence.

After these two interests integrated into my world, I realized how they capture my psyche. Sign springs a glimpse of another culture into my life, teaching me to constantly imagine and view the world from different angles. Writing empowers me to channel those interpretations into my voice as a writer. I’m not sure if I have a way with words, but I have my own way with words.

Tess Jacobson, who became a graduate of The Trevor Day School today, will be a freshman at Tufts University in the fall.

Puzzles in Action

By Sadie Stern

“Where’s Sadie?”

When I hear my name, I automatically know Justin is stirring up trouble in the classroom. This time, I barely see the pencil as it whizzes past my face, just grazing my hair before clattering to a stop on a nearby table. The noise captures the attention of seventeen first graders, who turn their heads as another pencil takes flight. Amidst the peals of laughter, I find Justin now lifting a chair above his head in an Atlas-esque fashion. I rush over to him and gently pull the chair away.

“What’s wrong?” I ask him.

He glances at his feet, then gestures to his math worksheet, scowling slightly, “I can’t do this.”

It was my second year as a volunteer at the GO Project, a non-profit organization that provides academic support to children in under-resourced NYC public schools. Justin arrived on his first day overflowing with energy. I became the only one who could calm him.

Why me? Perhaps the answer begins outside the elevator of my apartment building when I was Justin’s age. The lobby floors were slick with melting snow from outside. I could hear my teeth chattering and ran ahead of my family. I impatiently pressed the elevator button as a neighbor trotted in.

“Are you excited to see Santa?” she asked, brushing snow off her hat. I shook my head.

“I am celebrating Hanukkah because I am Chinese,” I told her. There was a brief look of confusion before she regained her smile, “That’s sweet.”

I was an enigma to my neighbor. She saw a Chinese girl but had no idea I was adopted by a white Jewish woman. I realized at a young age that there was something about me people could not know by just looking at me. The concept made my head spin. However, the reality of my own identity inspired my fascination in seeing the depth in those around me. I wondered if Justin could sense that inclination, if he knew I saw him as more than a troublemaker. Regardless, I was glad he decided to trust and confide in me, inadvertently becoming another puzzle for me.

I adore puzzles. As a child, I always loved sprawling across the carpet and sifting through the piles of puzzle pieces. There was nothing more rewarding than the excitement of watching the image slowly appear and the feeling of satisfaction when I finished. I was eight when my grandfather introduced me to the sudoku puzzle in the New York Times. We sat side by side at the kitchen table, mulling over the apparently endless possibilities of numbers and sequences. We worked for hours, armed with blue pens and sparkly butterfly pencils. Eventually, he would tire of the activity so I would carefully fold the page of newspaper and tuck it into my back pocket where it would stay until it was solved.

The keys to solving a puzzle, I learned, were patience, perseverance and a willingness to experiment with new things. I spent weeks employing a similar approach trying understand to Justin. Our long walks in the hallway became an outlet for him to release his energy and our seemingly trivial conversations became my window into his frame of mind. Slowly, I pieced together the puzzle of Justin. Finally, it clicked: I never saw him without his Lego figurines! They were inseparable. And so, I rewrote all of his math problems. Now instead of adding up library books or apples, Justin counted Lego figurines. Yet no one could have predicted that he would grow into such a strong math student. Similarly, no one could have predicted that a policy instituted by a Chinese communist autocrat could have created the perplexing life I know today as a Chinese girl who celebrates Hanukkah.

Sadie Stern graduated from Little Red School House and Elisabeth Irwin High School today and will be a freshman at Brown University in the fall.

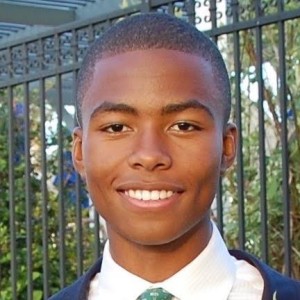

From Class Clown to Class President

By Drew Crichlow

“Should I do it?”

Incessantly egging on my friends and warming up my audience, I ask again, “Ready …? Here we go!” As I squat, I position myself to execute my next escapade. Today’s task: exploding a juice box.

There was always something inexplicably attractive about receiving attention, so throughout my childhood, the sound of laughter was my muse. I had an appetite for approbation (clearly not from teachers, but from my peers), and nothing was more satisfying than earning the missing-tooth smiles of my immature friends.

Seated politely at their desks, my poor classmates were trying to enjoy lunch peacefully, but what is a meal without a show, I thought. And with that, I plopped onto my juice box. Unfortunately, my stunt failed; the juice simply poured out of the container without creating the mushroom cloud of beverage I had envisioned. Despite this disappointment, my friends reacted just as I had expected, jumping to evade the anticipated blast radius, screaming in disgust, and the odd few, giving me the drug I desired most: laughter. The high was incredible, but my ecstasy was short-lived. Searching for smiles, I turned to see a less-than-pleased teacher who, hearing the disruption, summoned me with a beckoning finger curl. After being reprimanded, my antics led to another level of attention I had not anticipated. She chronicled my behavior in an email to my parents. Needless to say, my juice box bomb awarded me an ill-flattering but well-fitting behavioral report reflecting the day’s escapades.

In middle school, I could no longer get away with such blatant misbehavior. Instead, I disrupted class with lackluster jokes, only provoking laughter because of their inappropriate timing. But, I was soon struck by the gravity of being the class clown: my reputation was outweighing my innocence, defining my experience as a student, and compromising my academic life, despite my intelligence. The repercussions of my behavior were no longer worth the reward of a few chuckles. This recognition defined my maturation and freed me from my self-imposed shackles; I would no longer be a slave to laughter. It was time for the next chapter in my life, one defined by academic focus and exemplary school citizenship. This chapter (entitled “Self-Improvement”), was lengthy, but by the next chapter (“New Beginnings”), I emerged as a redefined character, one whose hunger for attention and laughter evolved into a thirst for knowledge and service. The more I focused on academics, the more I enjoyed learning; the more my peers and teachers believed in me, the more I wanted to give them a reason to keep their faith.

Ironically, being a class clown may be one of best things that ever happened to me. It shaped me into the person I have become, and helped me to develop my new muse: leadership. Leadership supported my maturation, as I began to realize I could positively influence my peers. My classroom antics gave me confidence and a voice to embrace public speaking – even though at the time, it was in a negative light. Being the class clown gave me the foundation I needed to be elected class president three consecutive years, and ultimately, president of the student body. Now, I am confident enough to represent the student body as its spokesperson to school administrators and make recommendations to improve the experiences of all students at school.

The transformation from class clown to class president was not easy, but revealed my full potential: I learned that actions speak louder than words, and new actions speak louder than old ones. In truth, I still appreciate laughter. However, I now recognize there is a time and place for everything, because integrity and citizenship take precedence over laughter. So while I am more mature, I will remember my class clown episodes as a souvenir – and as a roadmap for the rest of my life.

Drew Crichlow will be a freshman at Yale in the fall and just graduated from Montclair Kimberley Academy.

My Kind of Brain

By Melck Kuttel

Through the human eye, letters form up at attention, their ranks splitting off to make squads commonly known as words. Most can keep these letters at attention, preventing them from falling off the line. Yet, my page differs: the letters seem to dance. My eye lacks control, and my ranks fall into disarray. Words of grotesque nature form and then split off to form other unintelligible scribbles. I try hard but can only get the letters to make simple ranks for short periods, and then the renegades resume their crazed dance, defying my authority.

A child’s path to “readerhood” is crucial in helping him or her become a functioning member of society. Many children start the journey with clear skies and a calibrated GPS system, mastering key fundamentals at young ages. My journey was filled with snake pits and hailstorms. Many years went by and I was still battling the armies of vowels. After a semester of grade two in South Africa, a teacher recognized that I needed remedial help. I followed her recommendation to attend a school designed for kids confronting a difficult path to “readerhood.” I doubt I would be where I am today had I not followed this life-changing suggestion.

My journey as a dyslexic student has granted me the luxury of assimilating knowledge in different ways. After all, a curious mind can find answers in the most unexpected places. When I couldn’t rely on letters to conform, I focused on words spoken, landscapes traversed, cultures observed, and teachers dedicated to their trade. While I have become a strong reader, I am fortunate to have retained the ability to look beyond text and written words to find meaning.

Faces tell stories that are often in direct contradiction to the facts at hand. On a family trip to Kenya, we visited rural villages with people living below the poverty line on the global economic scale. Yet the joy and warmth radiating from those we met told a story of resilience and ingenuity. I saw, through the power of observation–the same intelligence beyond reading that I was compelled to develop when words would not join my army.

I have grown to have a certain level of affection for my dyslexic brain. How else could I accept the fact that a mistakenly inverted chemical formula meant to be a common household item, could end up causing a nuclear reaction? Only a dyslexic brain could easily discern the inversion.

It would take a versatile learning style, employing all my senses, to fully engage my global education. This style accompanied my dyslexia. I attended lower school in southern hemisphere sunshine in South Africa. School uniforms were mandatory, but shoes were optional. We played rugby and cricket, and had lessons in the shade of the canopy trees when it became too hot to be inside. On Flag Day we sang N’Kosi Sikeleli, and I carried an American flag on stage to sing “America the Beautiful.”

Then, at fourteen, I spent a semester at a ski program in Switzerland. I found myself gazing at the Alps wondering what possessed Hannibal to attempt them with his herd of elephant! This country with four official languages, had 450 different varieties of Swiss cheese, with further “variety within the varieties”, which the locals told me was a combination of vegetation and techniques passed from one generation to the next. We studied European history, and Swiss Mountain Guides taught us how to read snow and avalanche conditions. We watched weather to predict whether we would be skiing ice or powder from the way the crystals set up on our jackets. By then, I was a reader but reading comprehension alone could not have guaranteed success in these places. Thanks to my dyslexia, I had the foundation to employ multiple paths of engagement, which helped me draw as much meaning out of these experiences as possible.

Melck is a freshman at University of Southern California and a 2014 graduate of the Brentwood College School in Vancouver.

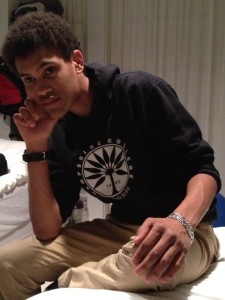

A Rough Field for Everything….Everything but Race

by Conner Chapman

A right arm hung from a body after our linebacker picked up the opposing quarterback and slammed him on the turf. The kid’s season ended with the nearly detached arm in front of my eyes. A year later, I rushed past an offensive lineman and dove for the quarterback. I missed. When I looked down, my mangled pinky finger barely hung on my hand. A trainer popped it back in, but I was done for the night. At least I had the rest of the season.

My finger still hurts, but not enough for me to abandon the sport. I am content playing football, not because of the brutal impact on my body, but largely since the game provides a level playing field where performance–not race–matters. Moreover, strong performance in football does not produce the remarks I confront for academic achievement, which are often blatantly couched in terms of race: “Now here’s a black kid who studies.”

Football isn’t a world free of problems. Yet on game day, my school’s black and gold are the only colors that produce team loyalty. If Trayvon Martin was on my team, he would have been safer on the field of broken fingers and arms than he was in the neighborhood where he met George Zimmerman. Moreover, if Martin confronted any brutality on the field, it would have been part of a play that had nothing to do with race.

A week after the not guilty verdict in the Trayvon Martin case, I was at a forum sponsored by Jack and Jill, an organization of black families. An elderly man yelled, “It was Trayvon Martin’s fault for being killed. He shouldn’t have been out at night wearing a hoodie.” I was shocked, angry and offended. This man was actually a black father of a teenager. I guess it was his way of saying “pull your pants up.” I stood and responded. “You are wrong,” I said. “There is no way you can justify Zimmerman’s actions or Trayvon’s death.”

After reflecting on the forum, I must admit it is only realistic to expect others to judge African-Americans based on prejudices tied to race and appearance. While the man’s comment felt outrageous, he raised a valid point, whether I liked it or not. If Trayvon had been wearing a suit, would his appearance have been enough to disarm some of Zimmerman’s racism, saving Martin’s life? This question is painful and disheartening, but real.

Unfortunately, I will probably spend my whole life disproving the stereotypes inside the minds of others. I will be forced to carry myself in a clean cut way that does not promote any triggers of black male stereotypes. In doing so, I will continue to be praised as an exception with compliments that don’t feel like real compliments. Achievements of mine are so often now called remarkable because I am black. This further inspires my appreciation of football where my abilities never wear a racial stain.

On the field, the roughness of the meritocracy inherent in the game compels players to think as a team regardless of race. The tough game provides a field where 22 players find equal opportunities to perform once they are in the game. However, I refuse to rest my laurels on football and allow centuries-old stereotypes to dictate my fate. Part of my life’s mission is to destroy barriers that confine blacks to narrow opportunities.

Coming home from a big win recently, my teammates were too happy to remain quiet. We sang, rapped, and made fun of each other and the coaches in jest. It didn’t matter whether you could sing or rap and, as usual, we were a team of only two colors–black and gold. I hope to create avenues where this kind of moment–so unburdened by race– is the norm. If only I could bottle that spirit on the bus and spread it worldwide.

Conner Chapman, a graduate of Long Island’s St Anthony’s High School, will be a freshman at the University of Chicago in the fall.

Meeting the Angel of Death

by Monet Thibou

I was hit with the biggest tragedy of my life on Columbus Day of 2010. My mother died. I entered a new home and was thrown into a new, independent school in the middle of my sophomore year. However, the school no longer felt new when I was elected student body president two years later.

It still feels like yesterday when my mother said to me, four months before her death, “I have cancer,” she managed to say with a shaking voice. “Don’t tell anyone, Mo.”

I honored her wish and went on with each day as if her hair weren’t falling out more and more with each doctor’s visit. I went on as if her skin wasn’t changing to a lighter shade of brown. But we did everything that summer, my mother, little sister and I. We took trips to Coney Island, ate fried frog legs on the boardwalk, photographed silly moments by the Cyclone, barked with ecstatic sea lions, high-fived underwater polar bears through the glass, and as if it were fate’s design, wore the same outfit to each event. Smiles and happiness swirled in the air above our heads as I pretended my mother wasn’t diagnosed with Stage 4 kidney cancer and not a soul knew.

It was arduous and draining, pretending, but it felt like the right thing to do. People would always ask: “Hey, how’s your mom?”

I’d simply respond, “She’s fine…” without any description of her “fine” condition.

She died physically and I mentally. All of her friends swayed with my family and me in different pews at the funeral as we tried to rock ourselves into a state of stability. After the funeral, I was dragged out of my familiar life, separated from my little sister, who now lives with her dad, and pushed into my second home with my aunt, uncle, grandma and cousin.

After my impromptu move from Queens to Brooklyn, my life began to pick up speed as my aunt enrolled me at Elisabeth Irwin High School. Stepping through the glass doors of Elisabeth Irwin felt like stepping out of the chaos from public school and through the gates of heaven; showing me a world I was never able to see before. Immediately, you could sense the change of dynamics in the air. The size of my grade dropped from 200 to 40 and for the first time ever in school, I was in the minority as a black female. On my first day, I followed the small, bustling crowds while keeping my head down as I walked through the halls. But, with time, I acquired a close group of friends. Then in May of my junior year, I was nominated for student body president and won.

My new life was exciting! The saying goes: “Success happens with a jump start.” But for me, it was a kick in the face by the angel of death. I would have never imagined living this life two years ago. But a child never wants his or her mother to go. I’m aware that I wouldn’t be where I am now without the tragedy of my mother’s death. But I’m glad that I’m succeeding instead of crashing. Through my mother’s death, I was forced to grow up, forced to be strong, forced to move on. In moving on, I, for once in my life, reached for stars and actually caught one.

Monet Thibou, a 2013 graduate of the Little Red Schoolhouse and Elisabeth Irwin High School, will be a freshman at Sarah Lawrence College in the fall. More of her writing can also be found on her blog: insertsomethingdeep.wordpress.com.

A Christmas Miracle

by James Thompson

I felt like a 12-year-old Danny Ocean or Robin Hood when I pulled off the most amazing Christmas heist. Maybe you can’t really call it a heist. I didn’t rob a bank, rip off a toy store or even steal anything physical, but things were stolen: the idea of my parent’s omnipotence, along with fragments of my innocence.

It all started when my younger brother, Calvin, requested my help to defy our parents. To a bystander this might have sounded like: “I’m sick of mom and dad telling us we can’t get an Xbox. We should buy one ourselves.” To me this sounded like: “I’m sick and tired of gravity, we should fly!” So to be clear: My brother asked me to help him do the impossible.

We plotted a Christmas miracle: to buy an Xbox, wrap it, and sneak it under our tree as an anonymous gift to the two of us. We began the normal holiday ritual on December 23 with the four-hour drive to my Aunt Debbie’s house in Yorktown Heights, New York. Once there, Calvin and I immediately went to work, with adrenaline as our companion throughout the entire process. Disbelief bathed my parents’ faces when we opened the final gift on Christmas morning. Mom and dad spent the rest of that Christmas in astonishment; guessing and re-guessing which relative could possibly have defied their expressed contempt for video games.

This was quite the moment for me, a guy who always enjoyed being a nerd. Even today, that n-word doesn’t bother me. I had been an obedient child, but was growing bored with my allegiance to my parents. The Xbox was the symbol of victory for my emerging tween rebellion. It became the first time I saw my parents defeated, and immediately a new fear emerged: How could those who couldn’t even stop me from buying a game console protect me from the world? It was a frightening and empowering moment.

The heist happened around the time I awakened to a new interest: film. In the Seventh Grade, I took a media literacy class, which captivated me as we studied the power of the media over the mind. We looked at commercials and explored the rigor entailed in creating 30 seconds of film that influenced such wide audiences. I was amazed to learn that such a large team of professionals invested so much intellectual capital on a commercial or a film–so much more energy than Calvin and I employed on the Christmas miracle. I did not draw this connection so neatly then. Yet looking back, I see how the two experiences shaped my coming of age. The heist demonstrated the power of my creativity while film would become the way for me to exercise that power in a constructive way.

My interest in film continued to grow with me and I convinced my parents to send me to a one-week intensive at the New York Film Academy the summer before my junior year. We learned to make short films with each student producing a two-minute silent film. My film focused on a college student who knew he was shortly going to die and how he chose to spend his final day.

The thrill of staging a world and sharing it captivated me. My nine hours in the editing room felt like nine minutes. I couldn’t get enough of shooting the best footage and editing a story, which turned out to be incredibly difficult. I relished the challenge. I felt like I was boxing with Mike Tyson and dodging every punch he threw sometimes even sending him through the roof with an upper cut.

I carried my passion for film back to school my junior year when I noticed a problem: a clear divide between white students, who are mostly residents of Brookline and students of color, most of whom are bussed to our school. I thought film was the best way to address this issue. Rather than write a paper for my Race and Identity class, I produced a film on the conflict by interviewing students from all races. As one of the few African American students who live in Brookline, it was easy for me to gain the confidence of both residents and bussed-in students.

I approached the documentary with a romantic view of film and the medium’s potential to help bridge the divide. When I finished the film, I was proud, yet underwhelmed and sobered by its limitations in solving the problem. I had a similar feeling after completing the Christmas Day heist. Both the film and the heist were driven by excitement but ended with my confrontation with harsh realities. The film didn’t solve the problem, it just illuminated it by highlighting the unintentional prejudice against students of color at my school. I could only expose a problem–not fix it. But exposure is a big part of progress and the first step to finding any solution. Six years ago, I learned that lesson through a Christmas miracle.

James Thompson is a freshman at Hampshire College and a graduate of Brookline High School in Brookline, Mass.

Cultural Combo: Bullfight and Bat Mitzvah

by Hannah Kliot

Imagine James Holmes, the man responsible for the Aurora shooting, thrown into an Olympic-size stadium and stabbed by men on horses to the cheers of thousands of spectators. If that seems too brutal for someone who murdered twelve people, why is the massacre of an innocent bull worthy of a cheering crowd?

I could not escape this question in Portugal. I am a Portuguese-American – or, as some call me, the only Portuguese Jew that they have ever met. I was in for a shock when my cousin invited me to a bullfight while I was working in Lisbon for the summer on my own. While initially hesitant to witness the barbaric cheering of an innocent bull’s death, my curiosity and endless fascination with different cultures overcame my hesitation.

I met my cousin at the front of Campo Pequeno, the bullfighting arena, with my 10 euro ticket in hand. The plain-looking door belied what was behind it: a huge stadium lined with food vendors and excited spectators roaming the endless halls in search of their seats. It was the NFL or NASCAR of Portugal – people argued over seats and tickets and cheered loudly for their favorite cavaleiro, or horseback rider, before the fight.

The excitement was infectious; I could not resist it. I tried to imagine my mom at my age. She grew up in Lisbon and went to bullfights most Thursdays. For her, this tradition was akin to my family’s weekly ritual of exploring a restaurant in a different neighborhood. I probably inherited my innate distaste for bullfights from my dad’s side of the family; his mother is Australian and his father was Latvian. Both sides have inspired my perpetual thirst to understand different cultural customs. So naturally, I sat in the stadium consumed with a question: How can people watch the maiming of an animal as casually as Americans watch Eli Manning throw a football?

I came close to finding an answer to my question during the intermission. A young man no older than 25 approached and hugged my cousin. I immediately recognized him as one of the cavaleiros who had been fighting in the arena just minutes before. My cousin then spoke with an older man who looked strong and proud as the young man ran back to prepare for his second round of the fight. Later, she explained that the older man was the boy’s father who was a very successful cavaleiro when he was younger. Their families had an endless line of cavaleiros tracing back for centuries and it was a deep-rooted family tradition and a considerable honor in both their family and in their town to be brave enough to fight what was considered such a wild animal.

I looked at this alien young man in his gold embroidered costume and thought about how different we were. Then, with a wave of surprise, I realized that maybe we were not so different after all. I saw hints of myself in the young cavaleiro’s commitment to family heritage. I expressed this same respect for the other side of my family with my decision to have a Bat Mitzvah in honor of my grandfather. A Holocaust survivor, his Jewish lineage was of great importance to him and therefore to me, even though my mother is not Jewish.

A few months before the big celebration, my grandfather passed away. I chose to continue to study for my Bat Mitzvah – I knew it was what he would have wanted. In both scenarios of the bullfight and the decision to continue studying for my Bat Mitzvah, I gained a newfound understanding and appreciation for the cultures that make up who I am. While I am not going to be the next cavaleiro or a devout Jew, my appetite to probe and understand both cultures and society beyond normal expectations will continue to shape my identity.

Hannah Kliot, a 2013 graduate of The Dalton School, will be a freshman at Northwestern University in the Fall.

Ambulance Journeys

by Jordan Lassiter

I threw open the door of the school nurse’s office and Miss Soloway sprung out of her chair like an Olympic runner bolting out of the starting gate. She looked at me as if she saw a monster. Who could blame her? My face was covered in white hives the size of marbles.

“Take a seat,” she ordered, not looking at me as she fumbled through the medicine cabinet.

“My neck and face are very itchy. I can’t stop scratching them,” I complained.

“Is your throat tight?” she asked, again not looking at me.

“A little bit.”

All of a sudden, my heart stopped. Everything was blurry and she screamed in the hallway for help. She snatched a green oxygen tank, placed the mask over my face and grabbed the phone. I cried as I heard sirens in the distance growing closer. The next thing I knew, the uniformed emergency medical technicians stood over me with stethoscopes draped around their necks. Everyone seemed to know what was happening except me. EMT strangers carried me into an ambulance. Inside, one EMT swabbed my leg while another jabbed a long needle into my thigh. I asked questions but it seemed as though I spoke a different language. No one answered. They ignored me, yet they were all focused on me as the sirens wailed all the way to the hospital.

Six years later, I am a high school junior sitting in the ready room of the first aid squad in West Orange, the neighboring town where I now serve as the crew’s youngest EMT. Everyone laughs at the story of my allergic reaction to the Granny Smith apple I ate at lunch in the fifth grade.

“At the time, I didn’t know why they stuck me with an epipen or why my mouth was itchy,” I told them with a huge smile on my face. After 150 hours of training, every EMT knows the purpose of an epipen.

An alarm interrupts the story.

I put on my stethoscope to prepare for my first call ever as a certified emergency medical technician. Within a few seconds, the sirens blare and the rig rolls down the street to Mount Pleasant Avenue. I sit in the back looking at the traffic we are free to pass. We slow to a stop. Kids from the nearby park gather around the fence to see what was happening. Police and firefighters surround the middle-aged man who suffered a seizure. My hands tremble. My face and my purple gloves are now filled with sweat. My mind goes blank. I am frozen. I feel sorry and helpless and the rigorous training fails me in this moment. I rely solely on the other EMTs to assess and transport the patient. My first call turns out to be disappointing.

The next day is miserable. My mind replays the call and I want to lie in bed all day. But I get up as I realize a new found respect for experience. A good EMT not only has the classroom training but practical and on-the job experience as well. Experience is powerful enough to overwhelm the nervousness that comes with inexperience. I aspire to be a doctor but as an EMT, I volunteer with electricians, retired military men, teachers, and carpenters. They know how to comfort people in times of distress. They analyze situations quickly. Only experience not self-pity can make me a better EMT now. I return to the Squad more humble and more confident with each call.

The journey continues two nights a week. As an EMT volunteer, I meet strangers who become memorable implants in my mind. There is the 90-year-old woman who stopped talking in the middle of a dinner with her son after a stroke. There is the kid trying to jump out of his bathroom window because his mother forbade him to see his grandparents. We convinced him not to kill himself. There is the 97-year-old man who lived by himself and fell down the stairs. He refused to go to the hospital, so we helped him to his bed and made sure he did not suffer major injuries, while he gave us good advice on how to be the best looking 97-year-old on the planet. Yet, the big moment arrives two months after the first call. An alarm rings and a surprise command comes from Chris, my tour chief: “Jordan, you are running the call tonight.”

I gathered the equipment and debriefed the other crew members on exactly what to do when we arrived on the scene of two cars destroyed after a head-on collision. I secured the scene, which means making sure my crew and I are safe to provide medical care to an elderly woman trapped in her car. She screamed for help and I helped her onto a backboard to avoid spinal damage. I assigned an EMT to examine her for head injuries and supervised as we carried her to the nearest hospital. She would not stop asking questions and yelling almost as loud as the sirens. Her cries were even louder than my cries had been in the ambulance after my allergic reaction to the Granny Smith apple, but they did not distract me from caring for her.

At the end of the call Chris came over to me as I put the equipment back into the ambulance: “Great job today. How does it feel to be on the care providing side of the calls?”

“Amazing.”

Jordan Lassiter is a Freshman at the University of Virginia and a 2012 graduate of Millburn High School in Millburn, New Jersey.

The Captain’s Steps

by Ashlynn Sarubbi

Thanks to me, we begin the same step over again. This is my fifth screw up. I reach my tipping point when the captain mocks me in front of everyone:

“Because of Ashlynn, we have to start all over.”

I can take no more. I grab my bag.

“Do it on your own,” I yell at her.

I’m quitting, I tell myself. But I do not make it out of the building without reconsidering my decision. I am not a quitter. In fact, two years later, the girl that messed up the steps that day— me —becomes captain of the Academy of Mount Saint Ursula Step Team. I trace my resilience to the eve of Valentine’s Day, 2005.

I am nine years old sitting on my bed wrapping candy in colored paper when the phone rings. My mom answers and then begins to cry. She grabs her stuff and runs out of the house. It is 8:00 PM. She never leaves the house this late. She returns hours later with news: my father is dead, the victim of a fatal bullet. Instead of crying, I sit in silence in the dark. He has already missed so much. He promised me that he would make it up to me, but he would now miss the rest of my life.

My mother is a police officer. My father was an ex-convict. For as long as I can remember, Dad was always the absent parent. He was imprisoned shortly after my birth, leaving my 18-year-old mother to raise me on her own. He was not released until I was seven. I sometimes found it hard to let go of the resentment. I had grown up without a father for so long that it became normal. Months before his death, I began opening up to him, and our relationship became stronger. He stressed the importance of never giving up and not making the mistakes that he made in life. He told me he had been offered a basketball scholarship to the University of Michigan. He chose another life that landed him in jail. He convinced me to be different and to create a better path than his.

My dad’s poor decisions eventually cost him his life. However, his faults helped me learn how to become the person he dreamed I could be. In reality, he had not let me down completely as he demonstrated what my life could become if I did not follow his advice.

My mother, on the other hand, has always been there for me. She grew up in poverty and was left to raise me alone. She eventually returned to college and became a police officer. My mother demonstrates the value in my father’s theory of not giving up. He didn’t live that life, but Mom displayed it brilliantly, and her model compelled me to stay on the step team that day. After all, my mother has faced many difficulties on her own. So I kept practicing those steps until I perfected them–even when it meant practicing longer and not going out with my friends. In doing so, I follow my mom who made choices that are the opposite of my dad’s. She shows me that it is possible to be strong enough to withstand even the most challenging obstacles and to stay clear of those who may be a distraction to me.

Two years ago, I was en route to leaving the building and quitting the team. Instead, I turned back, knowing that I could not be a quitter. It was not part of who I was or who I wanted to become. With the forgiveness of my coach and the team, I vowed to my teammates that I would never let them down again.

My father once told me I was a “Sarubbi” and I could be whatever I wanted to be. My big moment of triumph came last spring. I sat in a circle talking and playing around with my teammates. My coach called me to the hallway. I became very nervous. When we got to the hallway, he began a speech about what was expected of the team members and the captains. I thought I was being removed from the team. Finally, my coach announced that I had been promoted to Captain of the team.

Ashlynn Sarubbi, a 2013 graduate of Academy of Mount Saint Ursula, is a freshman at Franklin and Marshall.

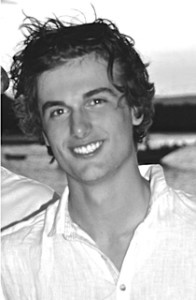

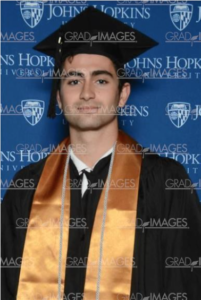

Climbing and Confidence

by Dexter Zimet

I feel alone on the football field of my team’s biggest rivals. Yes, it is just me, the only player on the field against the other team of eleven. They all run for me and the only line of defense is myself.

I get that feeling in many of my classes at Dalton. I am a rare libertarian amidst extremely liberal teachers and students. My economics teacher called on me to speak recently and, before my mouth opened, I felt the vicious glares of my classmates beam towards me as if I committed blasphemy. “I think trickle-down economics work,” I said. The stares grow into eighteen shouting voices: “How can you say that?” and “You’re wrong!” My resistance to censor myself forms my persona as a strong risk taker and defines my independence. Yet speaking my truth comes at the cost of some peers ostracizing me. However, taking risks prepares me for my dream to become an entrepreneur. The people in my life always warn me that the majority of start-ups fail, but I do not fear failure or risks.

Perhaps it all starts with living in a city with millions of opinions surrounding me. Everyday people attempt, in a New York manner, to push me to adopt their beliefs, whether they beg me to occupy Wall Street or argue that JG Melon’s makes the best burgers in the city or that the Yankees define the best in baseball. I happen to, dangerously, be a Mets fan.

In baseball, football, wrestling and snowboarding, some of my risks have produced consequences: three broken hands, two broken wrists, a torn right shoulder labrum, elbow tendinitis, a forearm stress fracture, shattered left elbow, a concussion, traction apophysitis, planter faciitis, shattered finger joint, two dislocated shoulders and two broken pinkies. Not bad for a seventeen-year-old, right? Through all the trauma I experienced, I had a smile knowing I had taken a risk doing something I loved. After all, if I survive physical therapy three times, I can make it through disagreements with my friends and teachers.

The test of this confidence came two summers ago. My friend’s dad invited me to climb Mt. Rainer. He warned that I needed to train extremely hard during the two months prior to the climb in order to prepare my body and mind. I kept telling myself that I would regret it for the rest of my life if I did not take this risk. The idea of not taking advantage of every opportunity was more frightening than actually climbing the mountain. I was galvanized. I began to eat healthier and I decided to never drink soda again. During baseball camp, I woke up everyday before everyone else to work out prior to the day’s activities. In Italy, I ran along the coast on narrow roads every night as strange looking cars zoomed by. With my dogs by my side, I sprinted up and down the rolling hills engulfed in the backwoods of our summer house. During these moments, I reflected on my mission to succeed by standing out on the field and in the classroom; risk was my vehicle.

I faced the first big test on a clear morning in late August. Our plane glided past the snow-capped monster and into Seattle. Qualms arose, as my pen scratched the release form. During training, we learned potentially life saving techniques, and I quickly realized other people were going to depend on me. I was responsible not just for my own life, but also the lives of seven others tied to my rope. The second day we climbed 10,000 feet and made camp. Lying in my sleeping bag, the sounds of howling winds and falling rocks kept me awake and pushed my nerves to thoughts of quitting. At 1:00 AM, we started the climb. At many moments, I wished to turn around and head back with the 20 out of 30 climbers who decided the trek was too much. At 11,000, then 12,000, then 13,000, my mind kept telling my body that we could do this. If I were to fail, I would regret it for the rest of my life. As I trudged the last few hundred feet, the pain withered. When we reached the summit the satisfaction and joy I felt was indescribable as I saw both the space needle and the Pacific Ocean. Since that climb, I am in constant search of that feeling of achievement. My hunger for success has grown. I constantly crave the sensation I experienced in that last step to reach the top.

Dexter Zimet is a freshman at Johns Hopkins University and a graduate of The Dalton School in New York.

At Home with Aging Books

By Alexandra Young

The smell of the aging paper, sweet and musty, almost instantaneously invigorates my senses. With the aroma alone, I can sense a history. When entering used bookstores, I look for the most veteran books. The more yellowed and thinned the paper, the better.

My love of used bookstores started with a walk with friends. We were killing time before the late-night showing of a movie. We came across a billiards parlour, but weren’t allowed to play because we were all 15. Then I saw it: a calvary of wooden carts on 12th street. As I came closer I realized that they were full of old books. I was so intoxicated by them. After 15 minutes of my chirping about how many books were there, Sarah suggested that we go inside. “There is an inside?” When we walked in the store, I was surprised to see how many people were there at this untimely hour. It was methodically chaotic; full of people, like me, hiding their true voraciousness. For 30 minutes in this place, nothing could distract my focus. I forgot about the movie until I was almost-forcibly dragged out of the store by my friends, who were entirely jaded by this scene. But for me, my appetite was not close to satiated.

I love used books for the same reason I respect Grand Central Station in New York City or the Cathedral de Notre Dame in Paris. They themselves are buildings with a purpose, a train station and a place of worship. However they are not just facilities, they are landmarks with a history and beauty. These edifices are visited, photographed and studied but are not sedentary. Used books are beautiful as entities; even the most worn out paperbacks are exquisite. They represent, to me, humans as we are, emotional souls rather than flesh beings. I am like a used book because I contain a story; the chambers of my heart are on their way towards yellowing with my own history. I am Alexandra.

I love history, and reading allows me to explore my passion for studying the past. Through both reading and history, I realize my own strengths are not solely based in my abilities, but in my desire to know more and the excitement I feel when stepping out of my cognitive comfort zones.

Second hand books provide a dual benefit: they contain the treasure of a story or piece of knowledge, and themselves are physical specimens of someone’s past experiences. It’s an added bonus if there are traces of the books’ previous owners — a name, a date, a location. While leafing through the pages, I am in fact giving the book a new life.

Why collect used books? Why not coins, stamps or some other collectible? It’s because I love reading. I crave to enter different worlds and leave with new perspectives. Even the most seemingly rudimentary text can provide me with a better historical, scientific or philosophical understanding of the world. As Betty Smith wrote in A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, “the world was hers for the reading.” Exploring the situation in Afghanistan through a fictionalized account of a young boy’s experience in Khaled’s The Kite Runner, gave me the understanding that no newspaper article or scholarly text could ever provide. Reading allows me to learn and love many different things. Every book helps me break into the stiff pages and rigid spine of the book of Alexandra.

Alexandra is a graduate of The Hewitt Schools and a freshman at Tulane University.

Seeing the Game of Life Differently

by Blair Weintraub

As much as I remember my first seizure, my last one was even more memorable. I was 12 and it was one of the first times my parents trusted my sister and me to be left home alone. I was curled up in my bed watching a movie when I felt the familiar tingling of my body and numbness of my tongue, and I immediately recognized what was about to happen. I tried to grab my phone, but it was too late––the numbness enveloped my body and the twitching took over. Like always, my brain was fully conscious, but lacked control.

Focus on getting help, I kept telling myself, as I spent all my energy on unsuccessfully attempting to roll off the bed to attract my sister’s attention. Breathing was harder than usual. The severity of the attack was worse than ever. My doctors had promised I was seizure-free, yet I was feeling the same fear and hopelessness I remembered too well. It felt hours had passed until my sister finally rushed to my side. She stared at me with a look of fear and confusion then grabbed my phone and called our parents, who instructed her to put a cold washcloth on my forehead and to not leave my side until they got home. She held me and whispered into my ear, telling me to focus on breathing and that everything would be okay.

I had my first seizure when I was five. Doctors eventually prescribed strong medications that made me tired and dizzy. I could only play sports leisurely. My dreams of following in my mother’s footsteps as a squash junior champion were shattered because I would be unable to train. Reading and photography became my new outlets. I sat behind my camera as I photographed the sport games I so eagerly wanted to play. I was too embarrassed to tell anyone I had epilepsy because I thought it would make me different and, at that point, different was bad.

Ironically, epilepsy helped me to appreciate my life. I had to spend many nights in hospitals with kids much sicker than I was. These kids couldn’t go to school or socialize outside the hospital. We spent most of our time playing the board game Life. Unlike the game’s characters, many wouldn’t graduate college, marry or have kids. They lived through that board game. I once shared a hospital room with Eric, a boy my age who was near death. He would do nothing but stare at the TV all day, and sometimes cry. He would never leave his bed, which made me see the frivolity of my complaints about lack of competitive sports or late bedtimes.

I have come a long way since my last epileptic attack. When I was 15, I was officially declared healthy and was taken off all medications. I could finally play sports competitively. Now, I see the board game Life as a constant reminder to appreciate the opportunity I’ve been given to actually live.

To make up for all the school I missed battling epilepsy, and to compete against the kids who have been playing squash since they could walk, I often had to study and train twice as hard. It might be too late to have a top ten ranking, but this hasn’t discouraged me from being the best player possible. Having to face seizures and their implications as a child has made me stronger, giving me the fierceness to fight for what I want and the determination to overcome obstacles. I’m no longer embarrassed to tell people I had epilepsy. I no longer see being different as a bad thing. Whenever I feel disheartened after losing a big match or getting a bad grade, I remember the tingling feeling in my tongue, the lack of control over my body, and think about how far I’ve come since then.

Blair Weintraub, a 2014 graduate of the Brentwood College School in Vancouver, will be a freshman at Bates College in the fall.

A Lasting Friendship with Music

By Brandon Lloyd

I saw clouds of rosin dust rising in front of my violin. We played as if there was no tomorrow and, in a way, there wasn’t, since this was Mr. Eckfeld’s last concert as conductor. The songs were an understated culmination of his tenure at White Plains High School. His years of teaching dissipated into me as I played the uptempo selections such as, Allegro, Aus Holbergs Zeit, and Walzer, conveying the merry, high points in his career. The slow, melancholy, and somber songs such as Xyklus 3 sent another message: “Goodbye, my dear old friends.”

Yes he was saying goodbye to us, but not to music. Neither his retirement nor aging would sever him from his love and prevent him from a pleasurable moment with his own violin. This powerful reflection came with the transformative roles of the violin and guitar in my life. They became my models of optimism—instruments of the idea that good things can evolve from tragic moments.

It started when I faced the biggest milestone in my other passion: Martial Arts. JT Torres and Pablo Popovitch, two of the world’s best Brazilian Jiu Jitsu practitioners, were coming to my martial arts school. I have always idolized them in the way I revere Mr. Eckfeld, and I was thrilled to step on the mat with them. Before I knew it, I was in the mix, practicing takedowns and drills with Torres and Popovitch. It was surreal. I was getting up after showing my partner a submission, when I felt a sudden twinge and loud pop in my knee. I crumpled to the ground writhing in pain. I couldn’t get up with excruciating pain shooting up into my leg and knee. I have encountered gruesome injuries before, but nothing like this.

In the following days, the onslaught of bad news crippled my emotional state. My MRI showed that I had torn my left meniscus, which required surgery. I couldn’t return to Martial Arts for at least six months. For ten years, I had never gone a week without martial arts. Six months seemed unbearable!

Music lifted me from my despair. After surgery, I had copious amounts of time for my guitar and violin. Previously, I practiced music outside of school about twice a week. After the injury, I practiced every day. I began to see the notes differently as music offered what physical therapy didn’t: a way to express myself. The instruments became extensions of myself as I got lost in the music I played. The slow, downbeat pieces laced with somber and melancholy notes perfectly reflected and described my emotional state in the first weeks after therapy.

Yet, one small moment profoundly changed my outlook on music: the words of a physician’s assistant teaching me to care for my leg. “When you’re young you should make sure not to rush recovery and remember you won’t be able to do some of the things you can do now when you’re much older.” The words hit me while I was practicing guitar. I won’t be able to perform some of the martial arts techniques that require substantial skill when I’m older. Yet I could play my violin and guitar for years beyond retirement, just as Mr. Eckfeld can. His talent grew with age, as I hope mine will. However, my limitations in martial arts may grow as I age. Had the injury not happened, I may not have fully appreciated my future with music or the true meaning of Mr. Eckfeld’s last night conducting my orchestra. It was a moment emphasizing the potential for a long future with my instruments on my own terms. I may not have a career as a musician but the instruments will always be there for me to pick up and will offer a mode of expression.

Brandon Lloyd, a graduate of White Plains High School, will be a freshman at George Washington University in September.

Fit for Me

By Marlena Rubenstein

At 12, I could barely run across the gym without gasping for breath. So if someone had predicted that I would one day run 3.1 miles continuously, I would have rolled my eyes and mumbled, “Yeah, right.” That image was as plausible to me as the idea of playing “Ode to Joy” on the moon.

Back on Earth, lunch in a middle school cafeteria is hell by definition; my classmates made it worse. Carrying a plate filled with questionable-quality cafeteria food, I passed girls sitting at bare tables. As I silently scarfed down my food, I overheard nearby conversations: “Well, since I’m going to a party tomorrow, I’ll look better if I don’t eat anything today.” I opened my mouth to correct the error of their thinking…and then immediately decided to stay quiet. I knew that these girls didn’t want my input, and I wanted to avoid conflict.

I endured endless bullying throughout middle school because of my weight. The advice I always received was: “Don’t let the bullies get to you,” but in following that advice I disregarded the origin of the bullying – my size.

I cannot remember a single visit to our family pediatrician that did not include a lengthy, worried lecture about my weight; and though I agreed, I wanted someone to wave a magic wand and solve the problem for me.

In 10th grade I realized that my fairy godmother wasn’t coming, and that my health deserved my full time attention. So I flew across the country to spend six weeks in the summer at a place that helps kids like me, and I returned home forever changed.

My typical day at Wellspring began at 7am with ‘Mama’ Christine, my favorite counselor, knocking on my door. By 7:30am, we were downstairs stretching on the grass for our pre-breakfast hike. In addition to the standard goal of reaching 10,000 steps per day, we went around the circle and gave a personal goal, which had to be S.M.A.R.T. – simple, measurable, attainable, realistic, and timely. Whether we were running laps or kickboxing, we kept moving until lights out at 10pm. Silently, we would each walk to our rooms, close the doors, and collapse on our beds.

The end-of-camp 5K was on the day before my 17th birthday; it was mandatory to complete, but campers set their own paces.

The gun boomed, and dozens of people shot down the track. I jogged slowly, my breathing in time with my footsteps. I saw those who had sprinted off slow down or stop entirely, gripping their sides and heaving. I steadily passed them all.

At the 1 mile mark, my nutritionist Mia stood at the water table where runners stalled their inevitable return to the monotony of jogging. “Looking great, Marlena! Wanna stop for some water?”

“No thanks, I’m not slowing down. See you at the finish line!” I called out over my shoulder, more determined than ever to make it to the end. I completed the 3.1 miles in 36 minutes and 50 seconds, and have never felt a stronger sense of accomplishment. This race put the sugar-free icing on the fat-free cake of my transformation at Wellspring.

I did not change my life because others said I should. I made my decision in my own way, and crossed the finish line as a new person. Every aspect of my life has changed because of the discovery of willpower that I never knew I had.

On the plane home, I worried that others wouldn’t see the new Marlena. To my delight, I was wrong. Walking through the door, my little brother enveloped me in a hug and exclaimed with genuine surprise: “Marlena, I can wrap my hands around you now!”

He would soon realize that my change in size was only the tip of the iceberg.

Marlena Rubenstein, a 2014 graduate of The Hewitt School, will be a freshman at American University in the fall.

A Tale of Two Families

By Ryan Colella

The words “military” and “Indiana” scared me at first. I could not imagine myself in a state that felt foreign when my parents told me they were sending me, a lifelong New Yorker, to a military academy in Culver, Indiana. Eventually, the sweet words of a familiar, but foreign language, “Oofah! Cocoa Bella! Mangia!” would provide the foundation that helped turn Culver into a home.

I had heard those words every Sunday for as long as I can remember. The words signal a Sunday lunch at our grandparent’s home in the Bensonhurst section of Brooklyn. Relatives would come from all over the tri-state area to eat lunch with my grandparents. It never mattered how many people were at the table; everyone would be served and barely able to finish their meal. As soon as I arrived, I would poke my head through the door of the house, and my nose could immediately sense the pungent smell of mothballs. This rancid smell would startle most people, but to me, the odor triggered a smile and sniffs of comfort that were matched with the sounds of varied accents throughout Bensonhurst. First generation Italians were shouting in Barese, a southern Italian dialect, while the second generations were speaking in a loud, nasally Brooklyn accent. The third generations of relatives understood every word, but were only able to converse in English. Those family luncheons helped form my adaptability, which led to my inevitable acceptance of the new cultures at Culver.

My parents thought that a military school in the Midwest would broaden my perspective on life. I was alone and frightened when I arrived at Culver, enduring six weeks of new cadet training in the blistering summer heat of Indiana. However when the weather began to cool down, so did I, and my unit began to feel like my Tri-State Italian family. Yet the new family gave me something that I had never had before, brothers. I am an only child, so the idea of brotherhood seemed exotic. The memories that I had bonding with my Italian family resembled new moments with my Indiana family comprised of 17 new cadets. We not only ate every meal together, but also worked together by shining shoes and inspecting each other’s rooms to ensure that we would all be accepted into the unit.

My life had been significantly altered in a beneficial way. What I used to call soda was now considered “pop”, and what I used to refer to as cursing was now “cussing.” When I ate lunch with my grandparents every Sunday, I was exposed to only one culture. However, when I came to Culver, I ate dinner with people from Texas, Nigeria, Ohio, Indiana, Mexico, France, and Wisconsin, all at the same table. I still missed my Sunday lunches in Brooklyn, but I now realize that I discovered something just as significant in a new family that broadened my perception of the world.

As my Culver success progressed, I started to change major parts of my life. I used to be a diehard baseball fan, but I decided to put all of my focus onto one sport, which was football. Culver gave me the opportunity to be more independent, but my Italian family made me feel comfortable making this decision, which was so important and crucial to my progressing independence. The football team became another way that I built a community at Culver.

I still miss my Sunday lunches in Brooklyn, but I now realize that I discovered something just as significant in with my new family. Now, when my Brooklyn family members visit me in Culver, we always order a large pizza and feast in our hotel room together. It isn’t the same as the family meals that I cherished in Brooklyn. Yet it is a reminder of what Culver has taught me: family bonds come in many forms.

Ryan Colella is a graduate of the Culver Military Academy and will be attending Elon University in the fall.

The Summer Wind of Change

by Kennedy Austin

The summers I knew were gone. Instead of flip flops, I wore sensible pumps. Instead of immersing my toes in the cool waters of the Atlantic Ocean, I dipped my feet into adulthood.

When junior year ended, I didn’t feel that same tingly sensation of freedom and excitement. Instead I felt nervous. Ahead of me was a leadership conference, an elective summer-long math course, and an internship at South Bronx Health Clinic. All would be incredibly rich experiences moving me another step closer to my goals of combating economic inequity and a public health career. With a lump in my throat, I leapt forward, feeling eager yet anxious about how I might fit into new worlds.

My summer officially began with a train ride to Washington, D.C. Nominated by my dean, I was selected to be an AnnPower Fellow and attend the Vital Voices Leadership Forum where accomplished female leaders mentor 50 young women.

My application included a plan to develop a high school course on economic inequity for privileged youth. Over the past two years I have become increasingly sensitive to inequity in my environment. Traveling around New York City, I’d gone from seeing extreme privilege to seeing people scraping by within minutes. Following Hurricane Sandy, I carried non-perishables to families stranded in public housing while replaying in my head television images of people with resources sheltering in luxury hotels. Seeing people struggle while others wined and dined made me angry. Why should different income levels afford different solutions in times of disaster?

At the Leadership Forum I talked to women from all over the world: a congresswoman from Argentina, a presidential candidate for Cameroon, and a graffiti artist who uses art to prevent domestic violence in Brazil. I encountered the go-getter lifestyle by workshopping elevator pitches, developing platforms, and networking.

The encouragement of mentors and other fellows was life-changing. I cried every day because I had never felt such empowerment. I came home with stars in my eyes looking at my passion to tackle economic inequity and health disparities. I began my internship the following week.

I made the 90-minute trek from Brooklyn to the South Bronx Health Clinic in one of the nation’s poorest neighborhoods. I sat for hours at a lacquered wooden desk. My job was to approach strangers and cheerily ask them to sign up for trips to the farmers’ market, Zumba classes and nutrition workshops. Some said yes and never came. Others were forthcoming, politely saying, “Oh, well, it says you can’t bring kids — necesito a llevar mi niño,” or “I have to work.” To that I smiled, though it probably looked more like a grimace, and said, “That’s a shame.”

After weeks of incessantly pitching programs, participation was low. I told my supervisor that potential clients were forced to choose work over activities and urged her to change the activity times. She refused. I had to accept that I couldn’t change her agenda because this was her job and I was just an intern. However, it didn’t defeat me or the fervor I had gained from AnnPower. I still loved speaking to patients about programs every day.

Previous summers now blur together like dream sequences. I move freely from tightrope-walking on a college campus in between classes to manning a four-woman canoe in camp regatta, and eating Chipotle until my stomach hurt. Last summer, I didn’t frolic like I had in the past. I did not indulge myself in the ephemeral bliss of unadulterated liberty that only a child knows as vacation months. Rather, much like diving from a cliff, I plunged into the realm of career-building and risk-taking, and I grew. I put myself out there, spoke my mind, and pushed myself forward.

By summer’s end, despite their drabness, my sensible pumps had become more comfortable. So comfortable that I haven’t rushed to put my flip flops back on.

Kennedy Austin, a 2015 Graduate of the Berkeley Carroll School, will be a freshman at Wellesley College in the fall.